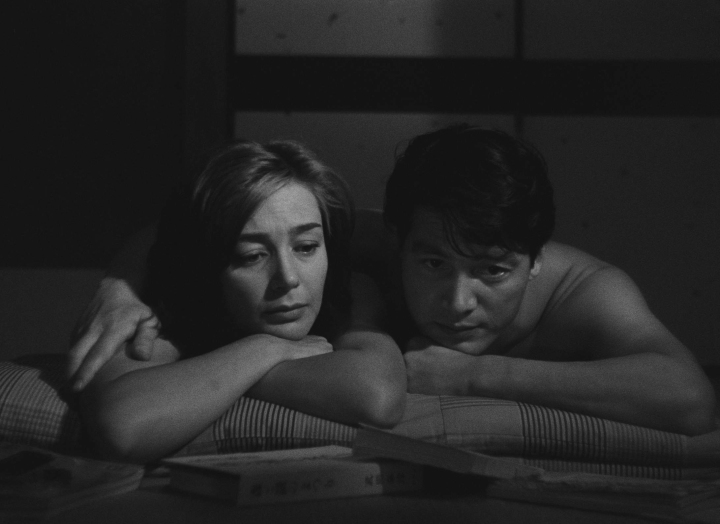

The Tea Room is dimly lit, low music humming in the background as patrons laugh and drink merrily together. A couple sits in a secluded area, fingers intertwined. They have only known each other for a few hours and yet it feels like an eternity. Hiroshima, a place that had not long ago known death and destruction, invites a French woman to share her shame and darkest moments with it, memories of the past still weighing heavily on the conscious of Hiroshima’s people and the woman alike. The man listens to her intently as she recounts a past that can only be likened to a personal hell on earth. Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) uses editing techniques such as flashback and montage in this particular sequence set in the Tea Room to present the viewer with clear insight into the mind of the woman. It explains to the viewer why she fears her own memories and why she, much like the people of Hiroshima, should embrace them in order to heal, influencing the audience to do the same in their own lives.

The sequence begins with the couple at a table in the Tea Room. The woman immediately begins speaking about Nevers, a cutaway to a river landscape shows Nevers as she narrates basic facts about it. “I grew up in Nevers. I learned to read in Nevers. I turned twenty in Nevers.” she says this as the scene cuts back to her at the table, the pretty view of the small town that she remembers is gone from the screen, establishing that the audience has free access to her mind and how she remembers certain events. This is a vital tool used to help the viewer feel connected to the woman and her pain, as they are now part of her life and privy to knowledge that the woman claims not even her husband is aware of. Her Japanese lover asks her about the cellar she was locked in, a straight cut to the small claustrophobic space once again helps the viewer understand and visualize Nevers, but this time it is no longer a beautiful image of a river and instead a gloomy nightmare the woman spent her youth trapped in. The cell is a small, dark space with a narrow window as the only source of light and the medium to close-up shots make it feel smaller still. The woman looks longingly out the window in a medium shot, her hair shockingly short and similar to the survivors of Hiroshima shown in the opening sequence. By this point in time the audience’s attachment to the character allows them to immerse themselves in the environment she is describing via access to her memories, which in turn will only evoke sympathy from the audience about the events of Hiroshima. Memories are often described as appearing in flashes inside the human mind, and Resnais embodies that with the use of flashback. As the woman begins to reminisce about her dead lover and her home, she realizes how truly painful it is to forget. In the same way, the audience is reminded to not forget such tragedies as World War II, and how human suffering only continues to exist in places like Hiroshima in 1959.

A close-up shot of the woman’s hands reaching for the man’s across the table juxtaposes with the next flashback of her fingers scraping and clawing at the walls of the cellar and then putting her wounded fingers in her mouth to suck on the blood. She describes that “hands are useless in the cellar” but her desperation propels her to continue this fruitless endeavor, hoping to somehow escape. The scene then cuts back to a close-up of the clean manicured fingers of the woman as they wrap around a glass of sake,she downs half of it in one go. The irony is that the woman is sharing her story to the man willingly, but at the same time is drinking alcohol to forget. The passage of time is apparent in these few shots, with the similar staging and focus on her fingers between the two shots aiding the audience in visualizing the shift in time. Also, aside from her stating that fourteen years have passed, the woman’s hair in the present has grown out, but her expression remains the same. Her hands still shake with a nervous energy, showing that time may heal the physical wounds, it does little to heal the emotional ones. Hiroshima also shows that it hasn’t fully healed, but is attempting to do so by creating peace films and a museum dedicated to the event as seen in earlier sequences, commemorating those who died.

The woman’s youthful appearance and carefree nature in the flashbacks are characterized by wide shots of her in open spaces, free and in love with a German soldier.When her lover is killed, these wide shots are juxtaposed and replaced with medium shots of the woman remaining static in a closed-off environment, like her room or the cellar, feeling trapped instead of free. In the present, close-up shots and her healthy appearance reveal that despite appearing healed, she is still very wounded and broken inside. These close-ups reveal her true despair, focusing on her expression as she relives her memories. These carefully chosen edits are powerful in making the viewer self-reflect and perhaps imagine how much the world around them has changed, from being a benign place before World War II and a hostile one during it. Though the war may be over for viewers in 1959, invisible wounds still bleed for many who remember and suffered, and forgetting about them would do little to help heal the scars still left on society.

As the woman continues to fall deeper into her own memories, the man assumes the role of her dead lover, a German soldier and enemy of France. A jukebox is turned on in the background, a diegetic romantic accordion piece begins to play as he questions her. “Am I dead?” he asks her, and suddenly darkness enshrouds her, as if she is no longer consciously present, instead far away in Nevers France. The lighting change is visible and immediate as she moves back and further away from the key light and towards the shadows behind her. As the sequence continues to cut back between the present and her memories, the shadows continue to cover more and more of her, signifying that she is becoming too involved in her own memories to be consciously present. “You’re dead.” she answers, and the lifeless figure of the German soldier appears on screen, and then it suddenly cuts back to her pained expression. As she tells the Japanese lover of each horrid moment, the editing is sparse with long cuts that let each event play out. The memory where she walks through a crowd of townspeople shaming her feels long and gruelling in order to achieve its desired effect of creating pity in the viewer for her. This is also the scene where the music starts to build, the diegetic jukebox getting louder as the people yell and laugh at her. It is at this point in time that she is unable to separate the past from the present; her memories taking total control. Finally, she emerges out of the shadows, symbolizing she is consciously aware of the present, screaming and is only quieted by two harsh slaps to her face, the music going silent with the sudden shock. Multiple cuts of other patrons turning to look at her only adds to the severity of the slaps. She smiles, realizing the past cannot harm her here, and the romantic melody begins to play again, as if nothing has ever even occurred. The editing so vividly reflects what reliving a traumatic event looks like with random cuts of footage that vary in length and subject without a temporal value given to them. It is up to the audience to determine the order and what makes the most sense to them. By including a short medium shot of her screaming out the window to a wide closeup of her in the cellar sitting quietly, it simulates how people remember events, which is in disjointed pieces. It also enables the viewer to lose themselves in the memory, her narration giving context to the shots of her despairing figure as she is kept hidden away from the town. The audience too is shocked out of her imaginings and brought to reality with the exaggerated noise of the slaps. The editing hypnotizes the viewer with its blatant simulation of memory, to recall their own past, something that most audiences of the time are reluctant to do as WWII is still too recent, inducing an emotional response that effectively establishes a connection between them and the film.

What Hiroshima Mon Amour represents is the importance of healing and the pain of forgetting. Resnais’ depiction of a broken woman’s inability to let go of her past serves as a metaphor for the people of Hiroshima, and how forgetting what has happened does not necessarily mean all emotional wounds have healed. As tragic as the atomic bomb destroying Hiroshima was, if it is not remembered and preserved by those who suffered through it, then all is meaningless. Resnais accurately encapsulated hurtful memories and translated it through editing into something meaningful for the viewers, creating flashbacks that so intricately provide visuals to the tragic backstory the woman tells. It can only promote an emotional investment in the story. The film also provides a narrative the audience can understand and sympathize with such as lost love and demonstrates how it is easily a parallel for the thousands of stories of Hiroshima and World War II survivors still unable to move on fourteen years after the end of the war. Perhaps even now, in a time where history is captured via cameras and the internet, we too need think about the events that changed us for the better and for the worse, and imprint them in our memory, not in our devices so that we can only move forward, never faltering on the path of life.